My last post described use of the Ideal Free Distribution (IFD) to analyze Late Pleistocene, early Holocene settlement of Prince of Wales Island (PWI), southeast Alaska. PWI is important because by timing and location evidence there bears on the Kelp Highway hypothesis for human migration into the Americas. The PWI data proved to be consistent with a second phase, early Holocene pattern of IFD settlement, but no archaeological evidence pointed to the predicted earlier phase of occupation. Schmuck and colleagues (2022) might have cited the inconsistency to discredit the IFD. Instead they used the model to buttress inferences that there is missing data, sites yet to be discovered. That kind of confidence in a simple model only partially confirmed begs justification. Another Alaska study is among those providing it.

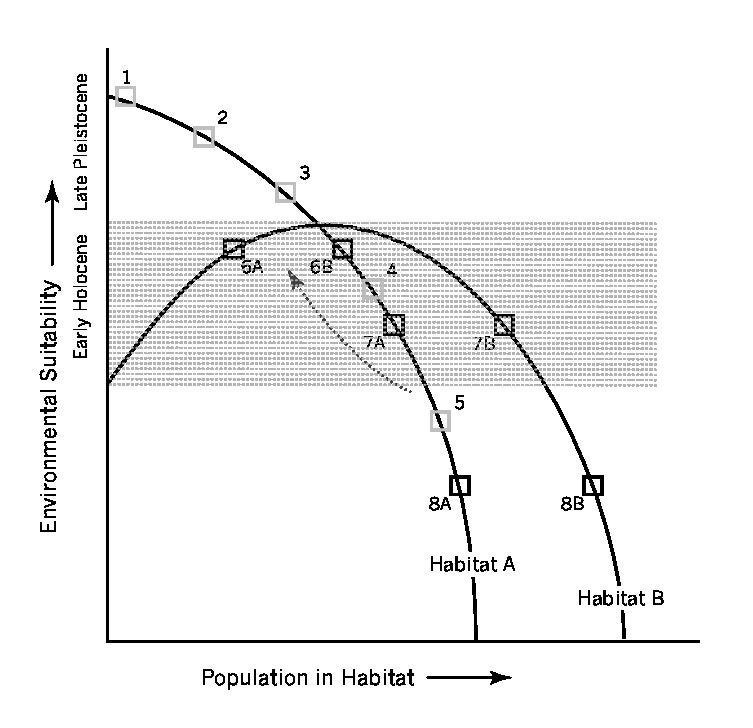

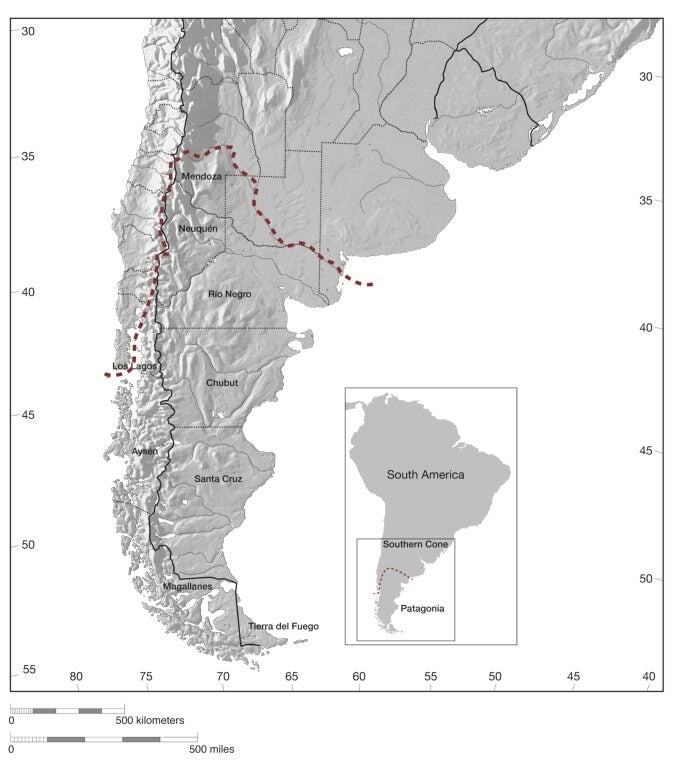

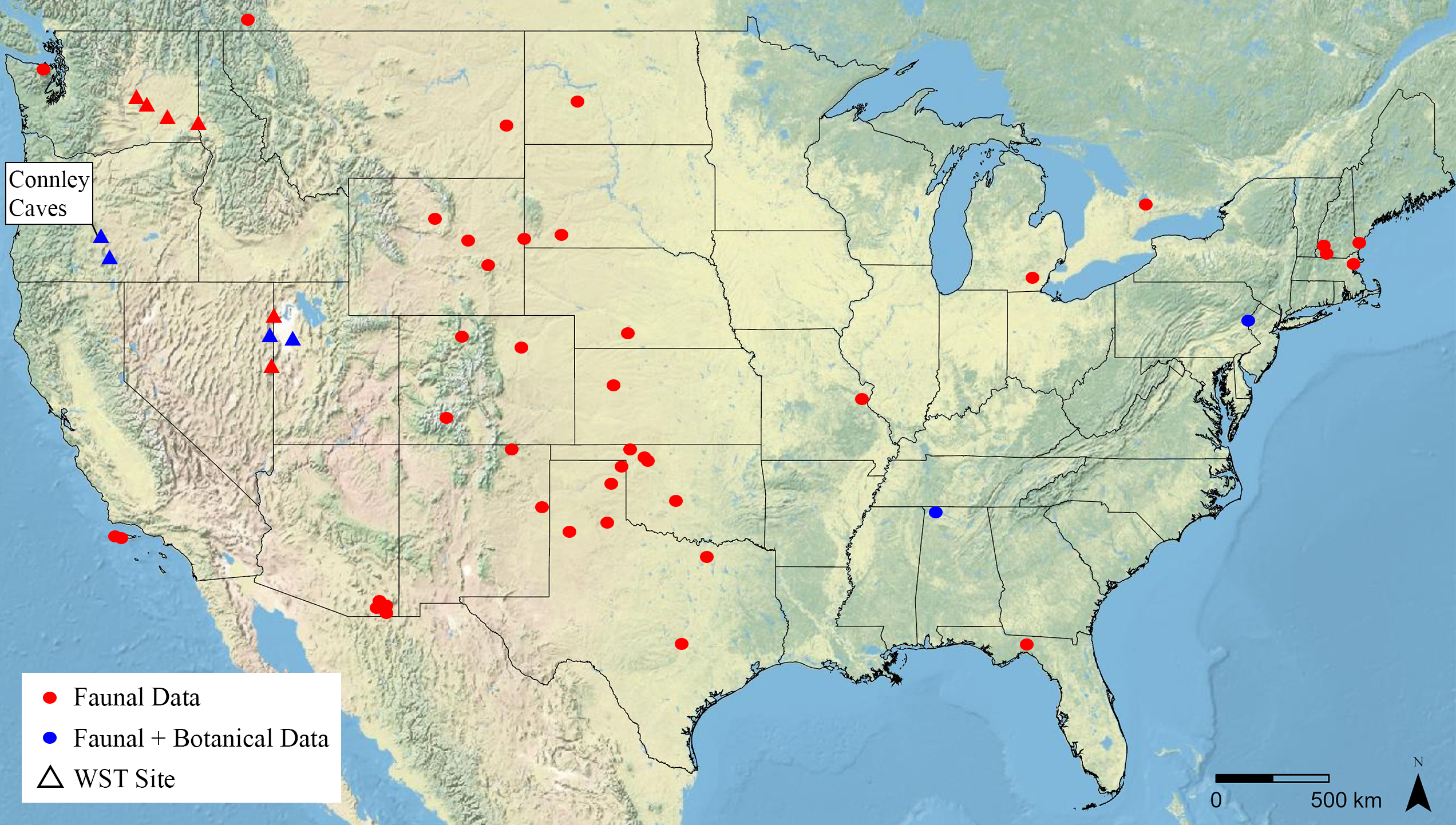

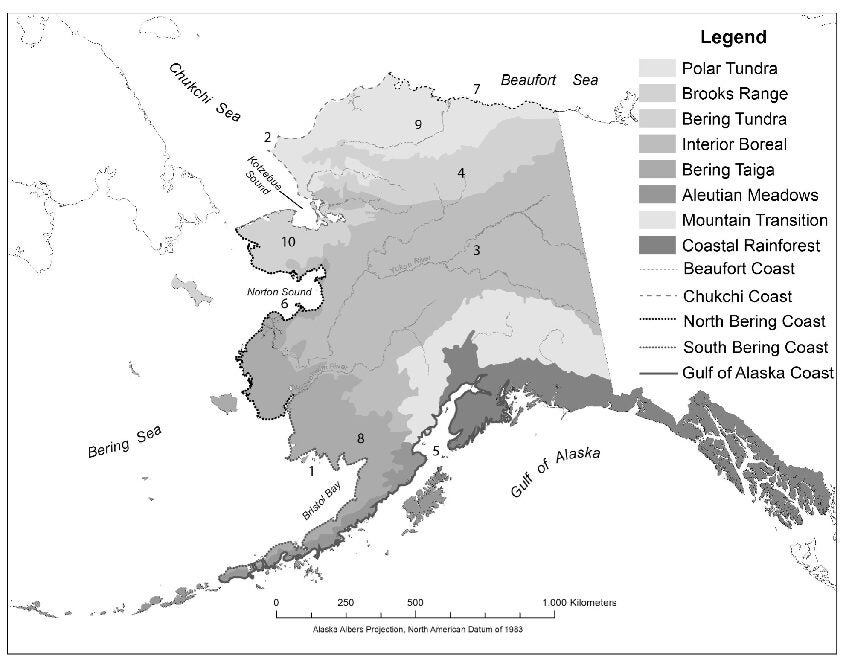

Alaskan ecological zones, ten of which were evaluated for large game subsistence suitability. The exceptions: Aleutian Meadows, Mountain Transition and Coastal Rainforest. The numbering corresponds to large animal, high-to-low rank order of suitability. Source: Tremayne and Winterhalder (2017, p. 84, Figure 2)

The Arctic Small Tool tradition (ASTt) population migrated from Siberia into Alaska ~5,000 BP, eventually becoming the first people to colonize the high arctic to Greenland, as well as the first to make routine use of arctic coastal habitats in Alaska. Tremayne and Winterhalder (2017) investigate how well the IFD helps to fill in the often disputed details of ASTt migration and settlement. We rank 10 ecozones — Beaufort Sea to Gulf Coast — by a standardized suitabilty index measuring large (> 30 kg) animal population densities (map); determine the earliest probable ASTt occupation in each ecozone by Bayesian methods and 775 radio carbon dates; and, we estimate population size over time by inventories of site counts.

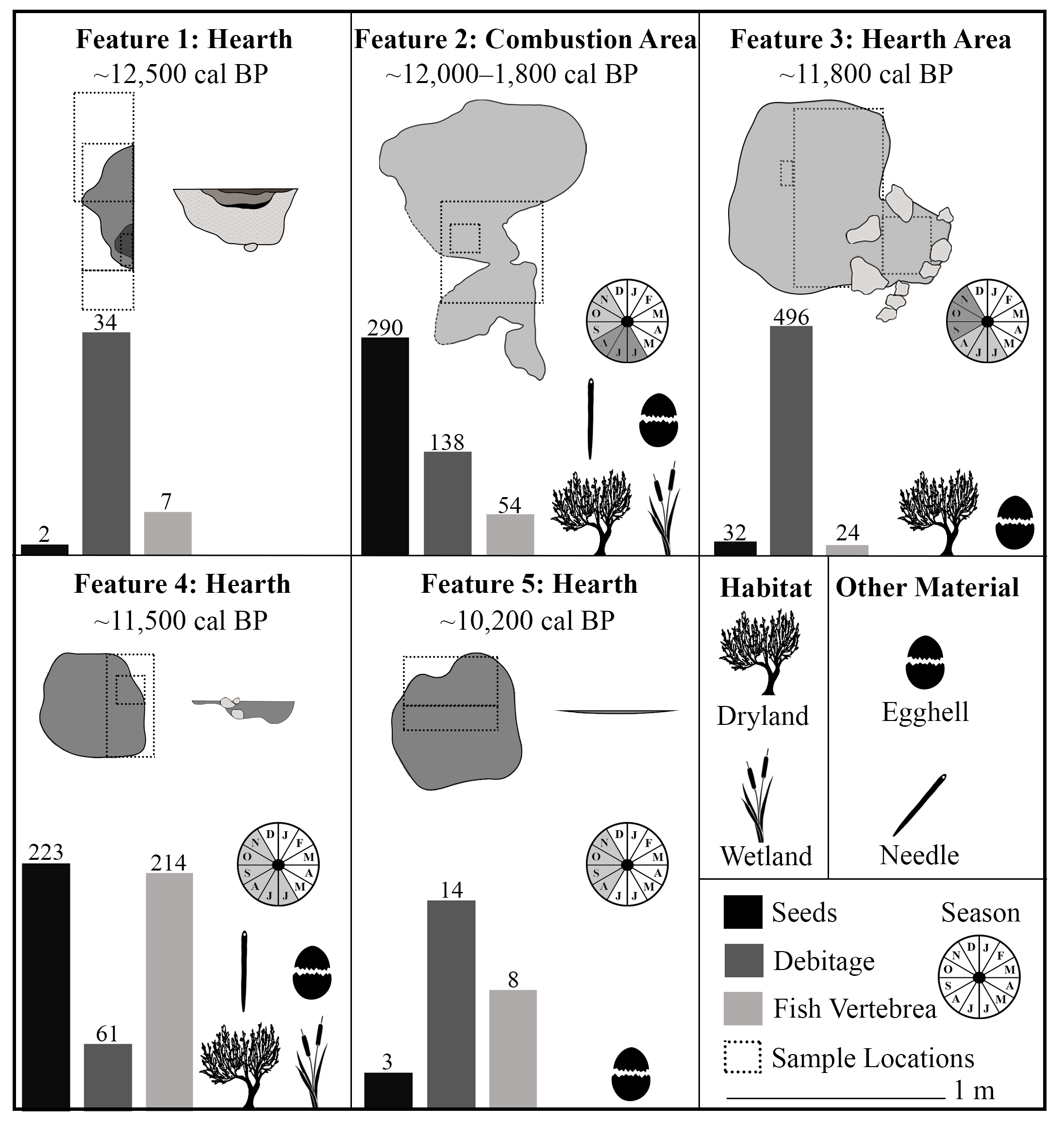

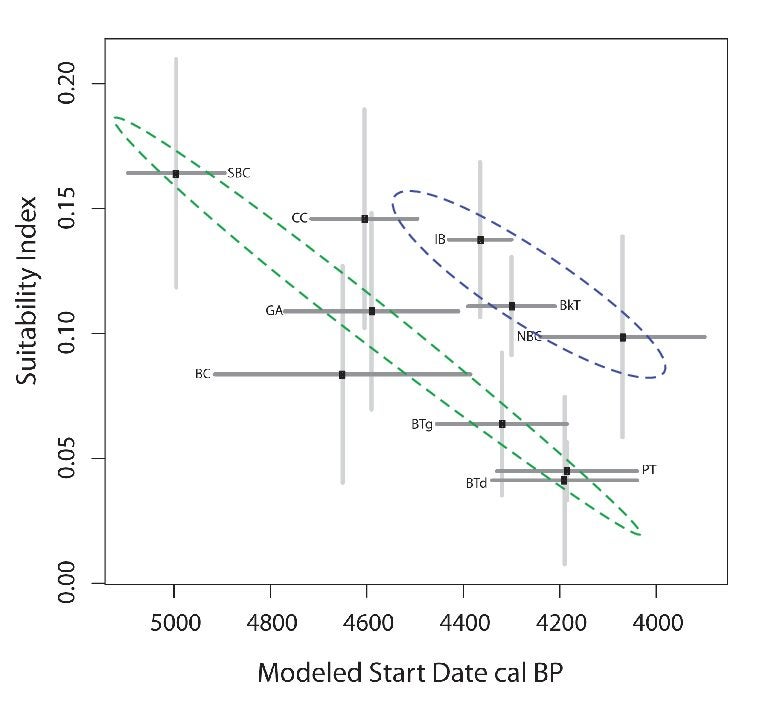

IFD representation, ASTt settlement of Alaska, showing ecozone suitability rank by date of earliest occupation. The main trend line (green dashed oval) encompasses initially unpopulated ecozones; delayed settlement occurred (blue oval) in already populated zones. Abbreviations, descending rank order: SBC-South Bering Coast; CC-Chukchi Coast; IB-Interior Boreal; BkT-Brooks Tundra; GA-Gulf of Alaska Coast; NBC-North Bering Coast; BC-Beaufort Coast; BTg-Bering Taiga; PT-Polar Tundra; BTd-Bering Tundra. Source Tremayne and Winterhalder (2017, p. 91, Figure 6).

Seven of the 10 ecozones establish a clear trend line in which the highest suitability habitats are earliest, and the lowest suitability the latest, to be settled. The three outliers already were occupied when ASTt migrants likely reached them, explaining why they uniformly are occupied late relative to model predictions. The vertical/horizontal confidence intervals evidence two important points: the model fitting analysis drew upon large radiocarbon and suitability data sets and, despite use of data with known uncertainties, patterns clearly are evident. The IFD accurately represents adaptive processes underlying the sequence and timing of a thousand years of ASTt settlement; it likewise demonstrates the ecological acumen of ancestral Native Americans.

Schmuck, Nicholas, Jamie L. Clark, Risa J. Carlson, and James F. Baichtal. 2022. “A Human Behavioral Ecology of the Colonization of Unfamiliar Landscapes.” Journal of Archaeological Method and Theory. doi: 10.1007/s10816-022-09554-w.

Tremayne, Andrew H., and Bruce Winterhalder. 2017. “Large Mammal Biomass Predicts the Changing Distribution of Hunter-Gatherer Settlements in Mid-Late Holocene Alaska.” Journal of Anthropological Archaeology 45:81–97. doi: 10.1016/j.jaa.2016.11.006.