Southern migration along the Pacific Coast and the Kelp Highway was demanding of adaptive skill; so too was what came next. The presumed off-ramps took a left turn into river drainages. Aquatic habitats were familiar, the transition marine to freshwater leaving useful skills that had been long practiced. Some of these rivers, the Columbia and the Klamath for example, reach far into the Columbia Plateau and northern Great Basin, interior environments novel to the new arrivals. How did they adapt? Here archaeologists build from the excellent preservation of dry caves on the margins of vast wetlands in the western high altitude basins.

Connley Caves, Fort Rock Basin (OR) looking north. After the rich marine estuaries and deep confir forest of the BC, WA and OR coasts, Paleoindian period immigrants quickly adapted to this quite different landscape. Image courtesy of K McDonough; photo credit, R Rosencrance.

Paleoindians in North America typically are portrayed as big game hunters. Bone endures; faunal analysis is a common archaeological practice. Although less evident and less commonly studied, carbonized seeds also endure.

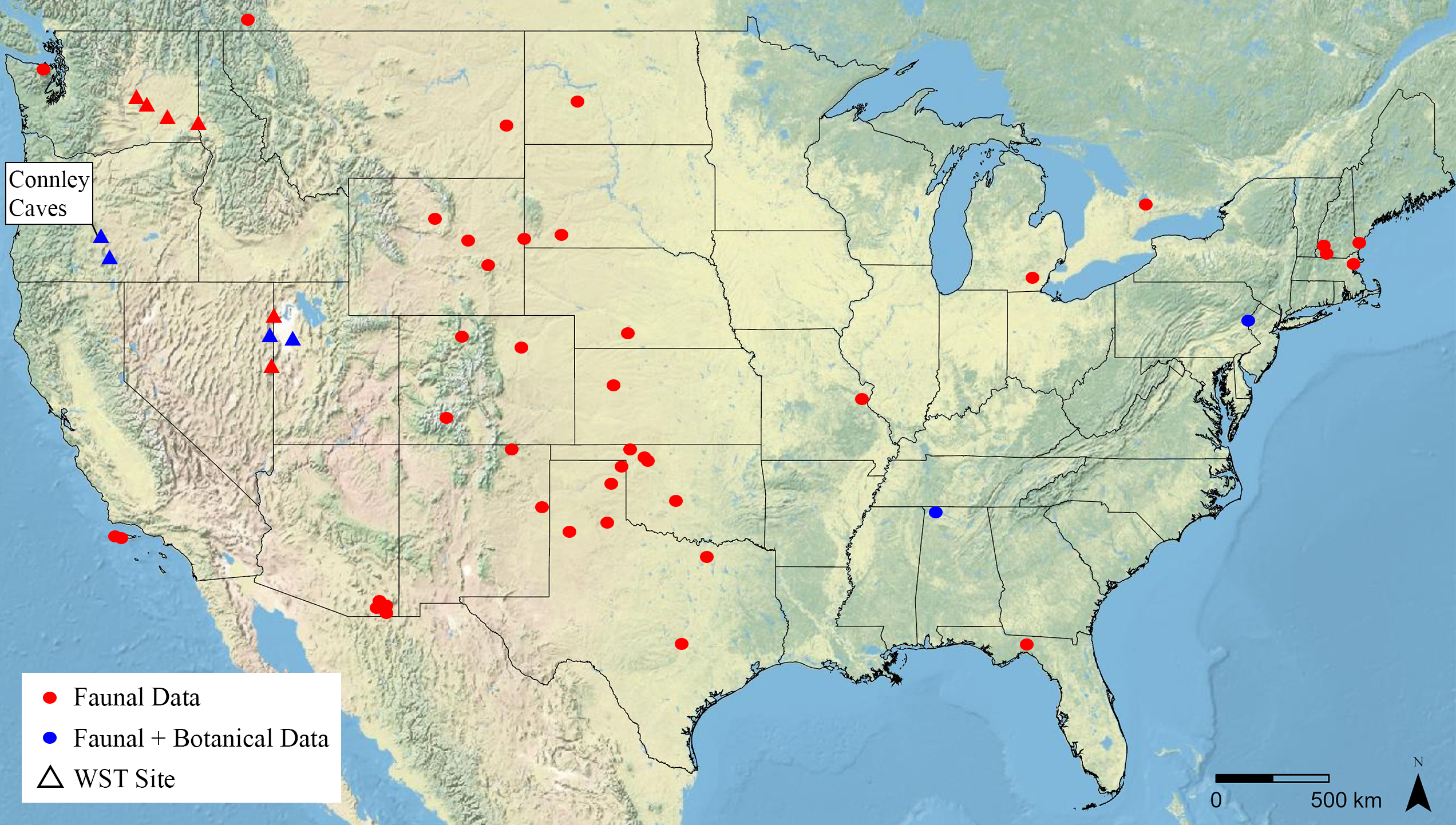

Location of Connley Caves and other Pleistocene-aged sites (> 11,700 cal BP) with subsistence data. Triangles = Western Stemmed tool technology; other tradition are displayed as circles. Botanical data from this early period (the blue site markers) lamentably are rare. Image courtesy of K McDonough.;

A bone needle fragment (a), seeds (b-w), sclerotia (x), and fish vertebrae (y-dd) recovered from Connley Cave combustion features. Image courtesy of K McDonough.

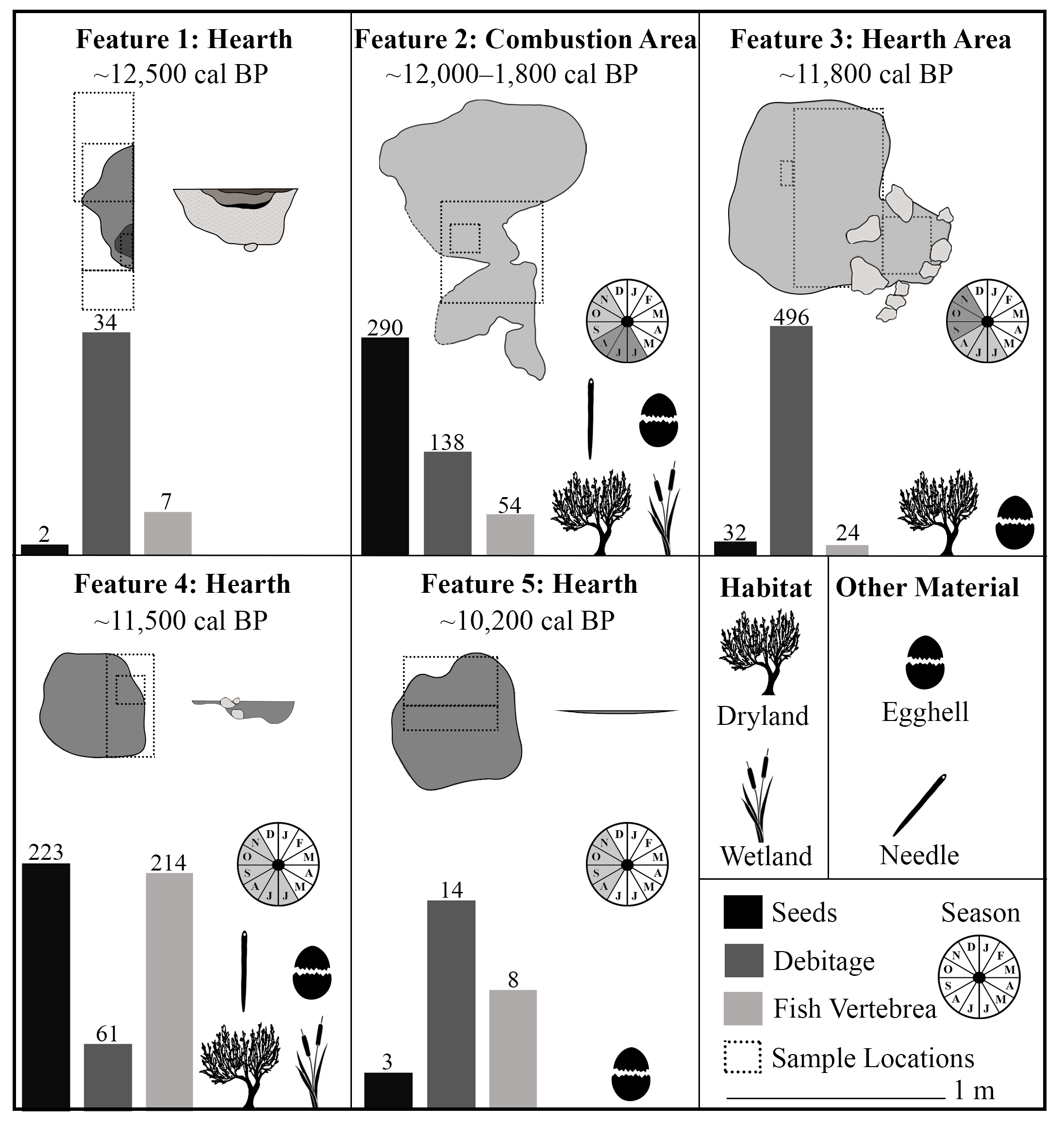

A new study (citation below) by ethnobotanists of 767 charred seeds recovered from firepits in Connley Cave 5, central Oregon, dated between ~12,500 cal BP and 10,200 cal BP, documents the use of 21 plant taxa. Of these, 18 are known from the subsistence practices of recent Indigenous societies in the region. Amaranths, cattail, grasses and mustards, likely were “important and perhaps even staple plant foods” (p. 19). Numerous fish vertebrae, the occasional egg shell, and the eye end of a beautiful bone sewing needle (p. 13, Fig. 7) also were recovered.

Seeds have the reputation in foraging studies of being low return rate foods; high gathering and processing costs can compromise their net kilocalorie value. Nonetheless, they are low risk, they can be stored, and — in a point emphasized by McDonough and colleagues — they are rich in micro- (vitamins, minerals) and macro- (carbohydrates, fats) nutrients. The Pleistocene-Holocene Transition (PHT) date of the Connley evidence suggests the Kelp Highway immigrants adapted to the interior landscape by carefully observing and then routinely gathering from its flora.

University of Oregon archaeology field school excavating at the Connley Caves, 2018. Image courtesy of K McDonough; photo by R Rosencrance.

Variation in Connley Cave 5 hearth contents, for the five analyzed features. Bar graphs show average number of seeds, debitage and fish vertebrae per liter. Habitat, seasonality and other items recovered are coordinated with the legend, lower right. Image courtesy of K McDonough.

McDonough, Katelyn N., Jamie L. Kennedy, Richard L. Rosencrance, Justin A. Holcomb, Dennis L. Jenkins, and Kathryn Puseman. 2022. Expanding Paleoindian Diet Breadth: Paleoethnobotany of Connley Cave 5, Oregon, USA. American Antiquity. doi: 10.1017/aaq.2021.141.

.